Published September 2009 Vol. 13 Issue 8

by Joanne Zuhl

additional reporting by Tim Covi

After housing authorities across the country reported massive shortfalls in funding, the federal government announced in August that it would provide an additional $30 million to people on Section 8 housing assistance.

The Department of Housing and Urban Development, or HUD, funds the Section 8 program through local housing authorities, like the Denver Housing Authority. People eligible for Section 8 housing enter into a lottery for vouchers. If selected, they then find an apartment with a participating landlord.

According to news reports and testimony before Congress, authorities across the country were saying they could no longer afford to provide housing assistance to tenants as the economic downturn overburdened their resources.

Published September 2009 Vol. 13 Issue 8

by Karolyn Tregembo

photography by Bill Ross

The city seems filled with vagrant kids, lounging on street corners, in parks, under bridges. I pass them on the bike trails and perched in front of the coffee house. Sometimes they ask for a dime or a bite to eat and sometimes I oblige. Some are just passing through, looking for a place to crash for the night. Others are faces I recognize and some I know.

Pony Boy sits on the sidewalk, playing his guitar, as much for his own enjoyment as for the passersby. At 17 years old, he is tall and baby faced, wearing a flannel and a mischievous grin. He is playing for enough change to get some coffee and maybe a sandwich. We have talked before, about how he never quite felt as though he fit in at home or school. As early as age 11 he found solace at punk shows and hanging out with like minds in coffee houses and the warehouse district. He says he has a place to stay right now, but finding a job is hard when you are young and don’t conform to social norms.

He likes to get out of the city sometimes and with no money in his pockets this is accomplished by jumping into an open boxcar. I am curious about the boxcar and he explains that he doesn’t really want to talk about hopping trains; he isn’t an expert and doesn’t want to give that impression. “There is a difference between living on the rails and catching a ride once in a while,” he says.

His friend, Banjo Fred, agrees, “I am still young and not yet fully experienced in the ways of the road, I have no right to pretend otherwise.” At 19, Fred is already a wanderer. He is good looking, quick-witted, and wise beyond his years. He tells me that he finds comfort and adventure in his travels, in going new places. I ask about a place to live, a job, possibly going to school. “There are things that get in the way of living frivolously, like sense and reason, both of which I cannot stand,” he says.

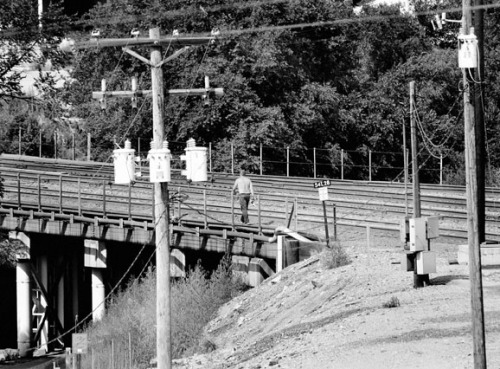

Huck Finn and Peter Pan with a modern twist. These two even hop trains. What could be more adventurous than jumping on a 2,000-ton piece of moving steel, heart pounding as it lurches and builds speed until it is carrying you at 60 miles per hour through vast, still undeveloped land. There is an obvious lack of sense and reason in stealing through dark train yards and thick brush beneath bridges to find the perfect spot to “catch out” (a term widely used to describe the act of catching a ride on a freight train). The excitement is in the unknown, in the anticipation of what lies ahead and often, in the very trains themselves.

A youthful desire for adventure and hopping trains isn’t anything new. At the height of the Depression 250,000 teenagers were wandering across America, a large number riding the rails in the hopes of finding money, food and shelter. Train hopping is reminiscent of a time when the economic upheaval of the Great Depression and the dust bowls of the Midwest left hundreds of thousands of people out of work and homeless. A time when the railways were filled with men, women and children riding box cars across the country.

Published September 2009 Vol. 13 Issue 8

Route 9

by Quinten Collier

Illustrations by Ross Evertson

Behind the rehab clinic and directly across the street from the work release compound, right on the dividing line between “Historic” Downtown Grand Junction with its fortress-like courthouses, octogenarian cottages and shop windows filled with irrelevancies, there lies the mute, oppressive warehouse atmosphere of the barren industrial district. Here, with the police station not a block away, amidst the street-hardened ex-cons and addicts, many with the famished eyes of those who have seen so much corrosion of the mind, body and soul they have ceased to notice anything else, with bestial tattoos like old war maps encircling their arms; here, in the desert heat that erodes the sidewalks, where 7th Street and South Avenue intersect, here is where a person looking to take the GVT (Grand Valley Transit) will find the main transfer point for busses.

I usually take the Route 9 to Clifton, a section of Mesa County composed of undernourished, deteriorating suburban neighborhoods, clustered trailer parks and stucco shopping plazas eaten by the sun. But I don’t often come to the transfer point. I did today just to see what it was like.

Published September 2009 Vol. 13 Issue 8

by Ross Evertson

All but one stop. After going all the way from ‘Aspen Grove’ in Littleton, past the Rossonian in 5-Points, and all the way down to wherever-the-heck it is at the end of the F Line—I couldn’t bear to take the last leg over to 9-Mile. While the C/D Lines briskly take you through the industrial corridor of Santa Fe Blvd, the F Line is slow, starting in a concrete valley west of I-25 and gradually turning into a tour of office park sprawl with bits of the prarie that said sprawl is consuming.