Feature: Catching Out

Published September 2009 Vol. 13 Issue 8

by Karolyn Tregembo

photography by Bill Ross

The city seems filled with vagrant kids, lounging on street corners, in parks, under bridges. I pass them on the bike trails and perched in front of the coffee house. Sometimes they ask for a dime or a bite to eat and sometimes I oblige. Some are just passing through, looking for a place to crash for the night. Others are faces I recognize and some I know.

Pony Boy sits on the sidewalk, playing his guitar, as much for his own enjoyment as for the passersby. At 17 years old, he is tall and baby faced, wearing a flannel and a mischievous grin. He is playing for enough change to get some coffee and maybe a sandwich. We have talked before, about how he never quite felt as though he fit in at home or school. As early as age 11 he found solace at punk shows and hanging out with like minds in coffee houses and the warehouse district. He says he has a place to stay right now, but finding a job is hard when you are young and don’t conform to social norms.

He likes to get out of the city sometimes and with no money in his pockets this is accomplished by jumping into an open boxcar. I am curious about the boxcar and he explains that he doesn’t really want to talk about hopping trains; he isn’t an expert and doesn’t want to give that impression. “There is a difference between living on the rails and catching a ride once in a while,” he says.

His friend, Banjo Fred, agrees, “I am still young and not yet fully experienced in the ways of the road, I have no right to pretend otherwise.” At 19, Fred is already a wanderer. He is good looking, quick-witted, and wise beyond his years. He tells me that he finds comfort and adventure in his travels, in going new places. I ask about a place to live, a job, possibly going to school. “There are things that get in the way of living frivolously, like sense and reason, both of which I cannot stand,” he says.

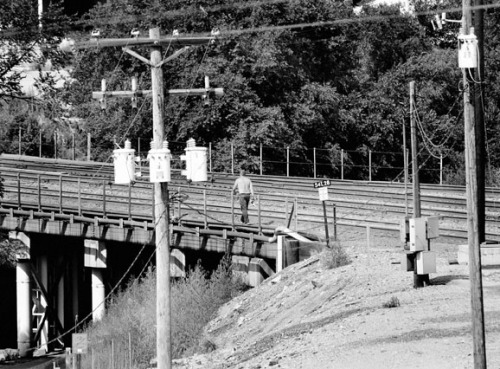

Huck Finn and Peter Pan with a modern twist. These two even hop trains. What could be more adventurous than jumping on a 2,000-ton piece of moving steel, heart pounding as it lurches and builds speed until it is carrying you at 60 miles per hour through vast, still undeveloped land. There is an obvious lack of sense and reason in stealing through dark train yards and thick brush beneath bridges to find the perfect spot to “catch out” (a term widely used to describe the act of catching a ride on a freight train). The excitement is in the unknown, in the anticipation of what lies ahead and often, in the very trains themselves.

A youthful desire for adventure and hopping trains isn’t anything new. At the height of the Depression 250,000 teenagers were wandering across America, a large number riding the rails in the hopes of finding money, food and shelter. Train hopping is reminiscent of a time when the economic upheaval of the Great Depression and the dust bowls of the Midwest left hundreds of thousands of people out of work and homeless. A time when the railways were filled with men, women and children riding box cars across the country.

Steeped in legend and the focal point of great cinema and literature, trains are at the heart of American folk culture. They are the backbone of the industrialized American landscape. Immortalized in the music of such greats as Woody Guthrie and Boxcar Willie, traveling and the Hobo lifestyle speak to homeless young people who feel a connection to the simplicity of past generations. There is mystery and a perceived freedom in the somewhat old fashioned monikers of Hobo, Tramp and Bum.

For most of America the romance is long gone and has been replaced with disgust and terms such as transient and vagrant. Some refer to our country’s homeless and traveling young people as Crusty Kids or Gutter Punks. Not quite as pleasant sounding as tramp or even bum, these “titles” give the impression of a lower caste, of people our modern American society has thrown away. Among these teens are those that are running away from something or have nowhere else to go.

Yet, as I spend more time with Pony Boy, Fred, and other traveling kids I discover that, more often than not within this culture, there are those who are in it strictly for the fun or the free ride. I am reminded that as long as there have been cars and trains, there has been a subculture of young men and women who engage in hitchhiking and catching rides.

Mike Riley, a thirty-year-old restaurant manager smiles as he recounts his first and only train hopping experience. “I was young and broke and I talked my friend into riding a boxcar to New Mexico. As we jumped off the train my friend injured his ankle and ended up in the hospital. I spent the next few days camping alone.”

For all of the romance and adventure, therein lies the reality that riding freight trains is dangerous. Just being in a train yard or near the tracks is dangerous. No matter what you have seen in the movies, jumping onto or off of a moving train is never really a good idea. Banjo Fred reminds me that his friend Jade lost her toes trying to hop a moving train. “It wasn’t the right moment, and she knew it even before she made the attempt.”

Freight trains are not built for passengers; only the engines are equipped to transport people. Rich Aguilar, an engineer with Burlington Northern Santa Fe Railway says “you find the smart ones riding in the rear DP (Distributed Power) engines, kicking back in comfort.” On more than one occasion as coal was dumped at an energy plant the massive pile contained a body. Seasoned riders know better than to get in a coal or steel car; you can be crushed or suffocated. They stick to box cars or the upper levels of car carriers. The Federal Railroad Administration’s Office of Safety Analysis reports that between January and May of this year there were 168 fatalities and 114 non-fatal injuries during incidents of trespass. By law, any unauthorized person in a train yard, on a freight train or on the tracks at any time is trespassing.

In the eyes of even the worldliest teen the greatest danger is not the trains themselves, though; it’s the Bulls. Varying by railroad, they could be security guards or federal officers. Like any member of law enforcement their job is to uphold the law, and it is illegal to ride on freight trains or trespass on railroad property. Many a Depression era tale involves being ejected from trains, arrested, strip-searched and shook down for your last dime “to pay your fare.” Modern stories range from being detained and ticketed to being driven to the middle of nowhere Kansas and thrown from a moving truck. Historically, most states in the U.S. have had strict penalties for railroad trespassing. The law became even tougher in 2001 when the introduction of the Patriot Act made it possible to label interference with mass transportation systems as acts of terrorism.

Loss of life and limb, fines, imprisonment; these are only a few of the many possible dangers in catching a ride on a train. I ask Fred why they take the risk when they could just hitchhike, bum enough change for the bus, or even ask a family member for a plane ticket. Another friend Travis speaks up, “Reliance,” he says. “You don’t have to rely on anyone else, you are traveling on your terms. Hitchhiking and scrounging bus fair causes one to be dependent on other people.” They are smart young men and they reassure me that this isn’t something they do very often now. Fred smiles, “Besides, how many little boys do you know that can resist playing with trains?”•