Published January 2010 Vol. 14 Issue 1

by Travis Egedy

In this digital age of hypermedia and endless consumption of temporary, throw-away culture, Drippy Bone Books are a breath of fresh air. Drippy Bone Books is first and foremost a publisher of underground zines, handmade Xeroxed art objects that carry their signature style of pop culture collage and child like drawings. Each copy is a thing of personal touch, love and care, a touch that is becoming increasingly foreign in mass-produced culture. Started by local Denver artists Kristy Foom and Mario Zoots, Drippy Bone is now based out of Amsterdam and Los Angeles as well, allowing a large mass of zine fans and appreciators to rabidly snatch up everything this extremely creative collective spits out. With zine titles such as “Whore Eyes,” “Sonic Bonk,” and “Bronze Legs” the collective have a playful approach to what they do, never taking themselves too seriously. I spoke with Mario Zoots and Kristy Foom about building community through art, what it’s like to be making your own books just for the love of doing it.

Published January 2010 Vol. 14 Issue 1

In the rugged hinterlands of Colorado, a Sheepherder has gone off the beaten path in a fight against one of Colorado’s lowest paying industries.

text and images by Jacob Ripple-Carpenter

Note: Employee names in this article were changed or omitted at their request for fear of reprisal.

Mentions of Western American culture conjure up images of corrals and Stetson hat-wearing cowboys with belt buckles the size of dinner plates riding broncos and bulls for eight seconds to the wild cheers of fans. You think of wide-open vistas, desert canyons, or mountains stretching as far as the eye can see.

Published January 2010 Vol. 14 Issue 1

text by Michael Neary

photography by Adrian DiUbaldo

Living at the Salvation Army Lambuth Center in Denver, Luz Hernandez and her two children face some uncertainty about their future. But uncertainty and all, their lives clearly feel better to them than they did last spring.

About six months ago, Hernandez was holding down two jobs while the family lived in a Westminster apartment. The jobs—part of an effort to emerge from a deepening financial trench—left little time for Hernandez to spend with her daughter Lesley Velasquez, 13, and her son Adrian Velasquez, 12.

“I would hardly see them,” she said.

Hernandez, who spoke quietly, seemed to relish the time she could now spend with her children.

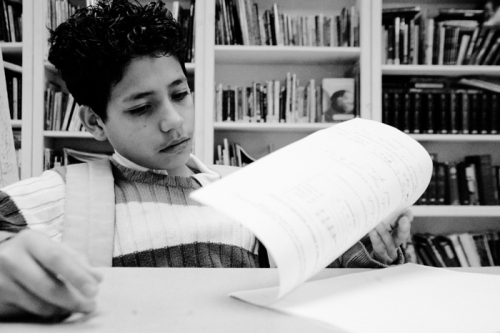

Hernandez talked about her move to the shelter as her son worked on lessons in a tutoring program begun this year by Denver Public Schools. Luz said her daughter, who wasn’t at the shelter that afternoon, would also be taking up the lessons. With wooden floors and modest but comfortable chairs, the shelter is an inviting place, and the moods of the families staying there seemed serene.

The children at the shelter are studying in ways they wouldn’t have been able to a year ago. DPS started the tutoring program where Adrian was learning with federal funds made available by the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act. The ARRA funds are part of a big increase in federal dollars available to Colorado public schools to help homeless students this year—but the problem itself is growing at a daunting pace.

Adrian Velasquez, 12, works on a math worksheet at the Lambuth Center.

Published January 2010 Vol. 14 Issue 1

Colorado Springs non-profits find alternatives to prison for juvenile offenders.

by Chris Bolte

Robert ran away from home at age 17, dropped out of school and couch surfed throughout the Colorado Springs area for four months. He was reluctant to talk about what, exactly, he did, so left it at he “got into trouble” and found himself in a treatment program through the Division of Youth Corrections. Through this program he was able to attain his GED and get started on a new path.

His circumstances are not at all uncommon. Dropping out of school has ramifications for young adults; idle time, isolation and even being cut off from many services provided for those still attending school. It can be a recipe for bad decisions.

Minor charges specific to youth are things like truancy or running away from home, gateway crimes. Some youth continue on this track to more serious crimes. They can be sent to the Division of Youth Corrections or, even worse, adult prison.

From there, if a youth returns to the same peers upon release, the same temptations to commit crimes and return to the system all over again are all but inevitable. This is what we have come to know as the recidivism problem.