Blind Justice

By Sunni Battin

28 years ago, Clarence Moses-El was sent to prison for a crime he didn’t commit.

What happens when those who lose years of their life finally find themselves free?

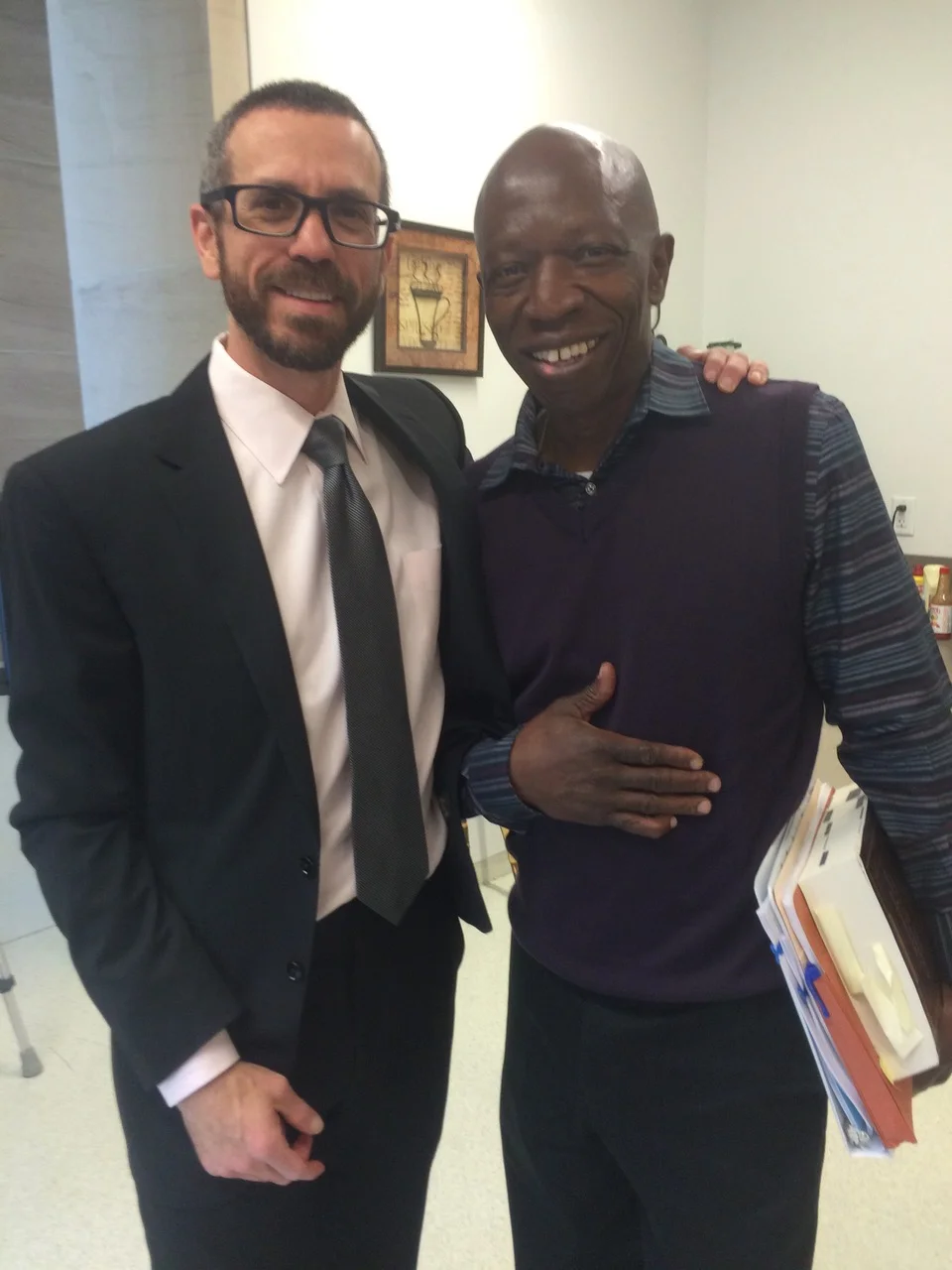

Attorney Eric Klein stands with Clarence Moses-El after a status hearing in Denver’s courthouse. (Credit: Eric Klein)

Time moves differently for those wrongfully convicted to prison. The days become a drudgery of memory and longing. Longing for the opportunities missed, the dreams unfulfilled, and the relationships lost.

Clarence Moses-El knows all about the memories and pain that accompany a miscarriage of justice. He lived it every day for over 20 years.

“Prison is more than a real human inferno,” Moses-El said. “From day one throughout this ordeal, I was tortured mentally in the worst form and experienced misery, anguish, pain, and sorrow. It was terrible hearing the repeated denials of relief. An innocent person accused of a crime walks in a shadow, like a cloud, where one is assumed guilty rather than innocent.”

An imperfect system

Moses-El finally heard the words “not guilty” in November 2016 after more than 28 years behind bars.

“My first day experiencing freedom after 28 and a half years was so unbelievable. A long nightmare had released its ugly wrongful grip on me.” Moses-El said.

Cases like his are not uncommon.

According to Brittany Williams, board member of the Colorado Innocence Center (CIC), an estimated five percent of the prison population in the U.S. is innocent. The state of Colorado estimates that there were about 20,000 total prisoners in the state as of 2017. This means approximately 1,000 prisoners in our state could be innocent according to the national standard.

“Wrongful convictions occur because it is impossible for the criminal justice system to be perfect. The fate of the accused rests on the judgement of people and people cannot be right 100 percent of the time,” said Williams. “Although some wrongful convictions are caused by purposeful acts — such as prosecutorial misconduct, false identification, false testimony, or less than par police work — other wrongful convictions are caused by simple mistakes. Mistakes are going to happen and innocent people are going to suffer.”

In the blink of an eye

Life for Moses-El in 1987 was about to be turned upside down. In what seemed like a blink of an eye, Moses-El was accused of beating and raping a neighbor in Denver. He claimed his innocence after the accuser named him the assailant. Though innocent, he endured multiple trials and years behind bars.

“I discussed my case with all who gave audience. I wanted people to hear my story. That was my plan,” said Moses-El. “Since I was innocent, I never had anything to hide about this case.”

Not only did Moses-El’s words speak to his innocence according to Eric Klein, one of Moses-El’s attorneys, but also his actions.

According to Klein, there were multiple holes in the prosecution’s case against Moses-El.

“The only evidence was an identification by a victim who had poor eyesight to begin with but who also had been beaten to where she could not see,” he said. “The first thing she told the police was that she did not get a good look at her assailant because it was too dark.”

It wasn’t until after a dream in the hospital, where she believed she re-lived the assault, that the victim named Moses-El as her attacker, according to Klein.

“She then awoke to believe that Mr. Moses-El, a neighbor whose wife the victim had problems with, was the perpetrator,” said Klein. “After her dream was the first time she had mentioned Mr. Moses-El.”

No other witnesses claimed to have seen Moses-El there. His blood type and DNA didn’t match that found at the crime scene. Still, he was convicted. From jail, he fought for further DNA testing to identify the true attacker, raising $1,000 from behind bars to fund the testing.

“In prison culture, prisoners do not talk about the fact that they have been convicted of a sex offense. It makes them a target for other prisoners,” said Klein. “The initiation rite for many prison gangs is to beat a sex offender. But Mr. Moses-El freely spoke about his conviction and the fact that he was innocent. If he got other prisoners to give him money for DNA testing and that testing came back with any result other than outright exoneration, he would have faced serious consequences.”

After more than 20 years insisting on his innocence, Moses-El’s story was about to take another turn.

“The major turning point was in 2012 when convicted rapist LC Jackson wrote Mr. Moses-El a letter that was essentially a confession. Unfortunately, the criminal justice system has a preference for finality. We now know that wrongful convictions are all too common,” Klein said.

Even though Moses-El has begun to reclaim his life, the damage has already been done.

“Being in prison wrongly convicted cost me valuable years away from my son and daughter; the loss of life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness; and the loss of an opportunity to get a good education. I’ve lost emotional and familial relationships with my siblings and parents. I can’t get those things back,” Moses-El said.

Just like it happened to his client, Klein said wrongful imprisonment could easily happen again.

“Wrongful convictions matter beyond the individuals who are wrongfully convicted. It is expensive, it wastes the good that an individual like Mr. Moses-El could be contributing to society, and it leaves actual wrong-doers free and able to perpetrate again,” Klein said.

Moving Forward

Five years ago, Colorado passed a compensation law to pay exonerees $70,000 per year served. That amounts to $1.9 million for Moses-El, which he is seeking.

Klein hopes his client’s case for compensation will send a message for prosecutors and police to always pursue justice rather than a conviction.

“Sometimes wrongful convictions happen because of innocent mistakes. But far too often, wrongful convictions are the product of a culture in police departments and prosecutor offices of winning at all costs,” he said. “We have an adversarial criminal justice system, but the role of police and prosecutors is to do justice, not simply to win.”

Colorado Attorney General Cynthia Coffman declined to give a comment on the case. “Anyone who has given an objective look to this case agrees that it is a travesty that Mr. Moses-El has spent half of his life in prison,” said Klein. “He has always been unbowed in his commitment to proving his innocence. He came out of prison dedicated to using his life and his experience to help others, and he wants to make sure that no one else has to live through the horror he lived through.”

Moses-El never wavered on his innocence. A jury eventually declared him innocent. No matter what, he refuses to be bitter.

“I am doing good,” Moses-El said. “My mind is right. I have a good relationship with my grandkids, with society, and with the grassroots programs I am involved with. I am enjoying life outside prison, making the best of things. I am doing things I never did before – walking in the park, watching the geese, helping others and giving back. I always try and stay positive.” ■

For more information on CIC, please visit: coloradoinnocencecenter.com