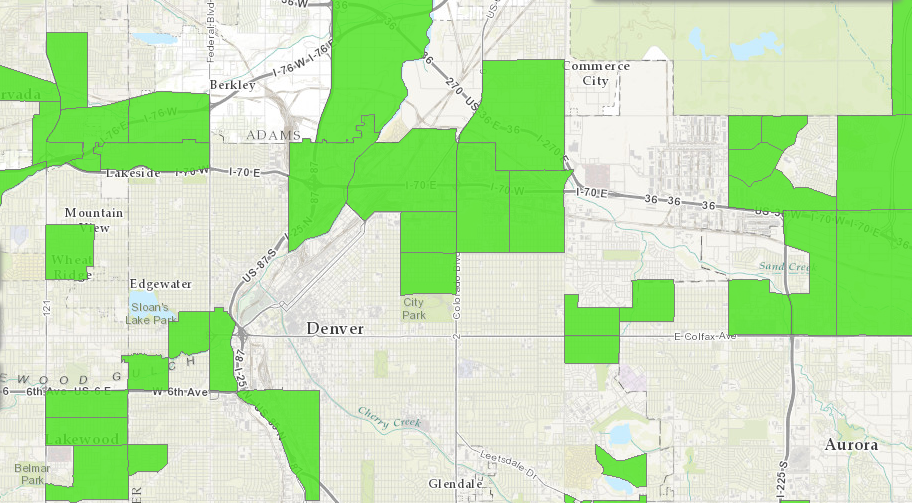

New Oases for Denver Food Deserts

By Matthew Van Deventer

Three neighborhoods are sprouting food co-operatives to satisfy demand in the grocery deserts of Denver and provide residents with affordable food that is both high quality and locally sourced.

A food co-op is a community-owned grocery store. Typically, co-ops are stocked with affordable and locally sourced foods and products, and are often located in low and middle-income neighborhoods. The members of a co-op are able to vote on decisions for the store.

The Northeast Co-op Community Market is finalizing its feasibility study and arduously seeking a permanent location around the Denver/Aurora border. Nearly a year after opening enrollment, the co-op currently has 680 members.

A onetime investment of $200, which can be done in monthly payments for as little as $25, qualifies a resident as an invested member. Members get special discounts and can vote on board members—among other perks. The co-op has developed a plan allowing qualified families to pay a one-time fee of $25 total for a membership.

Thomas Spahr is the chair of the board of directors, and reluctantly calls himself the leader of the community-led initiative. “We found it important to be able to recognize and treat all members equally and it’s part of the democratic process, but we don’t want to exclude anyone from participating,” explained Spahr. “We don’t want to create this big financial barrier, because $200 can be pretty significant.”

A seven-person board of directors oversees primary decision-making and also makes up part of a steering committee along with other volunteers. Volunteers are responsible for making everything else happen, including organizing events, presenting to community organizations, working on the financial plan, finding investments, selecting a location, and handling marketing efforts.

According to the business plan, the co-op is expected to gross $6 million in the first year and $10 million in five years. The co-op is seeking 10,000-12,000 square feet, a space half the size of an average Sprouts. Opening costs will run around $3 million, which will come from outside and membership investments.

Across town, community members in Westwood, a Denver neighborhood bordering Lakewood, are preparing to open a co-op early next year. Re:Vision, a nonprofit that helps educate communities about food, is helping the community plan the store.

Since 2007, Re:Vision has been holding classes on healthy eating, urban gardening, sustainable living, and community leadership. More than 400 backyard gardens have been planted in Westwood due to Re:Vision’s efforts, according to Cat Jaffee, the organization’s director of communications and public affairs, “incubating [a foundation] for the community to come together to build a grocery store of their own.”

The Westwood Food Co-op and Market will be a for-profit business and a separate entity from Re:Vision.

In May Safeway announced the closures of nine stores in the Denver Metro area—one of which was near Westwood. Westwood already had very few options for fresh and affordable foods. Moreover, the neighborhood is very diverse, with a large Hispanic population—another reason for a co-op that can be culturally focused.

Memberships for the co-op are $40 annually; community members can also purchase a lifetime membership for $200. A core group of 100 members met for the first time in July to discuss how to increase involvement and plan to open the co-op’s doors early next year.

“We think that the community needs to own the store. They need to have some skin in the game for it to succeed . . . making sure the community owns their decisions, that’s key,” said Jaffee.

In September 2014, the Denver Office of Economic Development gave Westwood Food Co-op a $1.3 million grant to purchase a 1.7 acre junkyard with 24,000 square feet of warehouse space, which will be used for the co-op’s store, distribution, co-working space, and a farm.

The Northeast Co-op’s trade area also has a very diverse population, with large Hispanic and African-American communities and refugees from Africa and Asia. Two-thirds of the population is considered low or middle-income.

“I find the co-op model has the flexibility to really address the needs of a population that isn’t homogenous,” said Spahr.

There is a King Soopers and Wal-Mart Neighborhood Center scheduled to move into the area, as well as an existing King Soopers in the Stapleton development. However, those stores don’t meet the standards of quality, price, and locally sourced that a food co-op does.

Spahr is confident the bigger stores will not impact the co-op: “A lot of the folks, regardless of socioeconomic status, desire something that is a higher quality yet competitively priced product and locally sourced.”

Many residents in the co-op trade area want to and already do grow their own food. The 2012 Colorado Cottage Food Act allows some Denver residents to sell homegrown and homemade items to the public or to a co-op. “The potential is fantastic,” said Spahr, “being able to share that with a wider community would be really exciting.”

Spahr is hopeful the city of Aurora will accept legislation like this, assuming the co-op will be located there since it would be less expensive.

Spahr keeps connected with the Westwood Food Co-op and the West Colfax Food Co-op (WCFC), which is only about a year into the co-op start-up process.

Warwick Green is on the WCFC steering committee and emphasizes a co-op’s unique freedom to listen to its members and provide. Currently there isn’t anything like a community center within the West Colfax Business Improvement District (BID), and Green feels like a co-op could fill that need.

“So really the big thing is that we want to be a food source for everybody in the community, get as many different people in the community involved so that we can create something that a whole variety of people can be interested in and feel like that’s going to support community here on West Colfax,” said Green.

In the boundaries of the West Colfax BID, between Federal and Sheridan on Colfax, there are no options for fresh food, aside from convenience stores; the neighborhood is considered a food desert. There was a large Hispanic market, but it didn’t last.

All three co-ops are looking at plans to leverage buying power amongst local famers to keep prices down, said Spahr, who had just gotten back from a meeting on the subject. Spahr has also built relationships with local hydroponic growers in the area and farms that aren’t so worried about getting the highest price, but more so getting their produce on shelves.

“What we’re trying to do is something a little bit more flexible, to meet the needs of a wider population,” said Spahr. ■