Feature: Crime or Punishment?

Published April 2010 Vol. 14 Issue 4

by Margo Pierce, with contributions from Kimberly Gunning and Ross Evertson

photos by Adrian Diubaldo

Economic profiling treats homeless people as criminals.

In 2007, approximately 3.6 million people were homeless at some time in North America, according to a number of non-profit organizations. “Homelessness” is defined in a variety of ways, so it is impossible to paint a uniform picture of what this reality looks like, but the numbers show that homelessness has reached epidemic proportions. And looking around the country, for many communities a popular response is punishment.

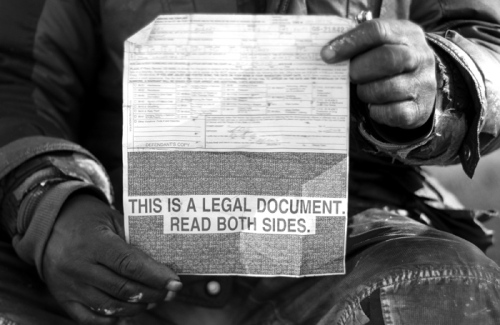

A man holds up a ticket in Denver for camping ilegaly . The ticket had no fine, but required him to go to Homeles Court.

A man holds up a ticket in Denver for camping ilegaly . The ticket had no fine, but required him to go to Homeles Court.

“It’s illegal to be homeless in this country. We have a form of economic profiling similar to racial profiling,” says Michael Stoops, director of community organizing for the National Coalition for the Homeless in Washington, D.C. “It’s a major problem, and it’s not going to go away unless citizens demand that their cities do something about it in a positive manner.”

What Stoops is referring to are a series of laws that have been created in municipalities across North America that criminalize homelessness. In many cities, the law treats certain necessary behaviors as “anti-social” when they are performed in public. Criminal citations are often issued to homeless people for activities that everyone else does indoors or on private property: earning income, sleeping, eating, going to the bathroom or sitting down to rest. Stoops calls these “quality of life” behaviors, and for people who live on the street or rely on shelters for temporary housing, they can be not only necessary, but common causes of tickets or even arrest.

Olympic Kidnapping

While advocates for the homeless recognize the harmful impact of such laws, most communities are slow to recognize the added burdens they place on people already struggling to overcome significant barriers. A single complaint can result in fines for homeless people even if they are causing no problems. When four police cars pulled up to an area under the Interstate 5 bridge in Sacramento, Calif., and police started ticketing the people sheltering there, Paula Lomazzi, editor of Homeward, the local street paper, was nearby. Lomazzi also works with the Sacramento Homeless Organizing Committee (SHOC).

“Safe Ground Sacramento was having a retreat about a couple blocks away when we received a call about this,” Lomazzi says. “We all took a break from the meeting to support the group under the bridge, including two attorneys. It was raining. The group that was camping/living under the bridge had moved there because their regular place was flooded out by [a] high river. They had nowhere else to go. Police gave them all citations and told them they had to leave. … We found out later that a lady that lives in the area had complained. This bridge underpass is not located near any residents or business. They were not visible from the street or anywhere else unless you actually walked under the bridge.”

Efforts to rid the streets of evidence of homelessness can increase during highly visible public events. The 2010 Winter Olympics in Vancouver, British Columbia, is an example.

“What we have seen in Vancouver is an escalation in the criminalization of poverty and homelessness in the lead up to the Olympics,” says Sean Condon, executive director, of Megaphone. “Homeless advocates believe this is an attempt to sweep the poor away during the games. While that hasn’t been fully actualized, it has led to displacement and further criminalization. The first wave started last winter when the police, taking advantage of transition in the mayor’s chair, started handing out tickets to homeless and low-income people in Vancouver’s Downtown Eastside—a poor neighborhood that is most well known for having an open drug market—for everything from jaywalking and riding a bicycle on the sidewalk. After a public outcry and the new mayor’s own opposition, the police finally backed off. However, this past summer they started another crackdown in the neighborhood on the vendors who sell often found goods on the street. Homeless/low-income people are unable to pay the $100-$500 tickets that were handed to them.”

A more benevolent label on another law recently enacted in British Columbia is the Assistance to Shelter Act, which authorizes police to “forcibly remove a homeless person and take them to a shelter when there is an extreme weather warning,” Condon says. With approximately 3,000 homeless people in Vancouver and approximately 1,000 shelter beds, plus a few emergency shelters, there are more homeless people than available beds.

“Dubbed the Olympic Kidnapping Act by locals, [the law] is troubling,” Condon says. “What the police, the shelter and the homeless person are supposed to do when all the shelters are full has not been answered. In fairness, the Vancouver police department has said they will not forcibly take a homeless person to a shelter and will only encourage them to go. But police departments in other municipalities, including other Metro Vancouver cities, have not made the same guarantee.”

As recently as December 2009, the Supreme Court of Canada has ruled in favor of the rights of homeless people. The court refused to reverse a decision made in 2008 by Supreme Court Justice Carol Ross, which struck down bylaws in the city of Victoria prohibiting homeless people from camping in public parks. She wrote that the bylaws “violate … the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms in that they deprive homeless people of life, liberty and security of the person in a manner not in accordance with the principles of fundamental justice.”

Housing is cheaper

There are no comprehensive studies proving that creating punitive laws around homeless activities improves public safety. In fact, research from the University of Denver using computer assisted mapping showed no significant change in crime before and after an anti-panhandling law was passed in Denver prohibiting panhandling in the downtown business district.

Advocates for the homeless, however, cite scientific research and anecdotal evidence to prove that addressing the root causes of homelessness—not the behaviors related to it—can have a positive long-term impact for the community as well as the individuals.

Homes Not Handcuffs cites a study in the Journal of the American Medical Association in which Seattle researchers concluded that it’s “cheaper to provide supportive housing to chronically homeless individuals with severe alcohol problems than to have them live on the streets.

“Researchers designed a study to evaluate the effect of a Housing First intervention for chronically homeless individuals with severe alcohol problems on the use and costs of services,” the report says. “According to the study, the median costs of Housing First participants before the study were $4,066 per person per month. When participating in the Housing First program, median monthly costs decreased to $1,492 per person per month, after six months and $958 after 12 months.”

Most large cities have more homeless people than shelter beds and even fewer services to address the root causes of the problem—mental health issues, addiction, job training, high unemployment rates, hiring practices that bar individuals with criminal records. Success stories are hard to come by.

The “A Key Not a Card” campaign in Portland, Ore., allows outreach workers from five different service providers to offer people immediate housing, instead of just a business card.

“From the program’s inception in 2005 through spring 2009, 936 individuals in 451 households have been housed through the program, including 216 households placed directly from the street,” says the Homes Not Handcuffs report.

Another innovative and successful program cited by the report comes from Daytona Beach, Fla. In an effort to reduce the need for panhandling, a coalition of service providers, businesses and the city of Daytona Beach provides homeless people with jobs and housing. The Downtown Street Team program hires homeless people to clean up downtown Daytona Beach. Each is provided with shelter and then transitional housing. Some of the participants have secured other full-time jobs and housing as a result.

Make them wear signs

Unfortunately, failed programs tend to get the most attention.

“What happens when a city proposes some new initiative to solve the homeless problem—and this is in a negative way, to criminalize homelessness—it passes,” says Michael Stoops of the National Coalition for the Homeless. “The chamber of commerce, the police department, the business community will say that this new anti-panhandling program is working. And then other cities hear about it. Cities are actually very lazy. They will copy and pass this same, exact panhandling ordinance that was passed in Cincinnati.”

Indianapolis and other municipalities are currently considering the ordinance Stoops refers to.

“In 2003 Cincinnati City Council passed an ordinance requiring panhandlers to obtain licenses from the health department,” says Gregory Flannery, editor of Streetvibes. “Teachers, nurses, activists and others registered as panhandlers in an expression of solidarity. The Greater Cincinnati Coalition for the Homeless (parent organization of Streetvibes) filed a civil-rights lawsuit in federal court alleging the ordinance was a violation of the First Amendment, which guarantees the right to free speech. In settling the lawsuit, the city, the Homeless Coalition and Downtown Cincinnati Inc. (DCI) agreed to create an outreach position at DCI, whose job includes connecting panhandlers with social services.”

Politicians in Cincinnati, eager to appear tough on panhandlers, have sometimes tried to ignore the conditions of the settlement, however. Last summer City Councilman Jeff Berding proposed taxing panhandlers and making them wear signs stating how much the city spends to help homeless people. In response to these conditions and other outrageous claims made in the proposal, Berding bowed to community pressure and retracted the measure, but only after a significant amount of grandstanding.

Advocates are working to change the views of lawmakers while simultaneously finding ways to get around the laws until they are removed.

In Sacramento it’s against the law to camp or use “camp paraphernalia” on any public property. Camping is allowed on private property with an owner’s permission as long as it’s not for more than 24 hours, according to Lomazzi.

One unintended consequence of the law is that people who own houses could receive citations for camping violations. If a family wants to have a two-day camp-out in their backyard, they can’t get a permit: The limit is one day. The likelihood of a neighbor calling the police isn’t great. But the net result is much more severe for homeless people. Even though Sacramento has more homeless people than shelter beds, people are not allowed to create their own shelter, denying them even minimal protection against the elements.

Sacramento Homeless Organizing Committee is trying to adapt.

“We have started a new organization called Safe Ground Sacramento that is trying to establish legal places for people to stay until housing is available,” Lomazzi says. “Campers stay together and sleep illegally most nights. A church has offered sanctuary to the group on freezing cold nights. Currently, the strategy is to go from one private property to the next … in hopes of evading the anti-camping ordinance by taking advantage of the 24-hour private property loophole.

“We set up a Safe Ground community on private property near the central city with the owner’s permission, and that lasted for about a month before the police came in and arrested everyone. The city threatened to fine the owner, so the group vacated the land.”

Support from the community in the form of donations for sleeping cottages and pledges for future financial support is coming, but locations for the rotating sleeping sites are not yet being offered.

Like other parts of the country, “No Camping” laws and anti-panhandling laws have been a common response to homelessness in larger cities in Colorado.

Boulder has been splashing the headlines with recent opposition to a decades old No Camping ordinance. In 2009, the Carriage House, a non-profit day shelter and service provider for Boulder’s homeless, found that the Boulder police issued 356 tickets last year for camping outdoors, and that people spent a total of 224 days in jail for unpaid tickets from camping violations. In response to protest, Boulder city council and the Boulder Mayor’s office have said that they are focusing on more long-term strategic plans to reduce homelessness, and don’t plan to make short term changes to the No Camping law.

On the other end of the Front Range, Colorado Springs just voted to ban camping in the city. In February, following passage of Colorado Springs’ No Camping ordinance, “Camper’s Village” was formed as a homeless transition camp. Mobile homes and RVs can be rented monthly for $400, and an area will also be designated to campers in return for participating in special programs. It is a for-profit initiative that will open to the homeless at the end of May or the beginning of June this year, following renovation.

Denver passed its own anti-panhandling ordinance in 2006, banning panhandling in the business district downtown, and has also restricted sitting and lying down in public rights of way. Rather than strictly policing and issuing tickets, however, Denver has adopted an approach of trying to connect the homeless with services. On the 16th Street Mall, where police officers have been trained to work with the homeless, reports about this process have been positive. But the Denver VOICE received several reports last year about possessions being disposed of when police told people to move away from illegal campsites along the Platte River. The scope of that experience is still unknown since only a few first-hand reports were made.

‘Everyone has the right’

At a time when millions are being donated by private citizens and government to offer relief to 1.9 million Haitians left homeless by the recent earthquake, some North American cities turn a blind eye to the policies that punish almost twice that many people in the same circumstance.

But change is possible.

“After two years of debate in front of the Commission of Human Rights of Québec, a victory has been achieved,” says Serge Lareault, publisher of L’Itinéraire, Montreal’s street paper. “On Nov. 9, 2009 the commission condemned strongly the city and the police regarding the social profiling of Montréal’s homeless. The government of Quebec engaged a new lawyer for homeless at the beginning of December 2009. He is charged with the creation of a center for drunk homeless as an alternative to help them and not arresting them or giving tickets. But the fight continues. The police still arrest and give many tickets each day.”

Homelessness has become a crime, but homeless people are the victims, not the perpetrators. Laws that worsen their plight aggravate the offense. Just as mental illness, sexual abuse and addiction are conditions that call for help—not for prosecuting victims—homelessness deserves a response rooted in compassion, fiscal sense and respect for international law.