Art Feature: Clark Richert

Publighed February 2010 Vol. 14 Issue 2

by Travis Egedy

Clark Richert is a lot of things to a lot of people. He is a Colorado institution who for the last 40+ years has been working as an artist, a scientist, a philosopher, a professor; and maybe most importantly, he’s an individual challenging his surroundings and the people who surround him to look deeper into what the universe really is, and how it works.

Richert is a man of enormous talent who has done much to shape the current art scene within Colorado. Working at the Rocky Mountain College of Art and Design, he has cultivated much of the progressive artistic talent that makes up this scene. As a professor at RMCAD within the fine arts department, Richert has been a profound influence on generation after generation of young and curious art students (full disclosure, I was one of those young and curious art students) who leave his classroom with a love of art, a knowledge of the contemporary art world, and the much needed encouragement to be themselves. His teaching style is one of a consistent optimism, where the students are taught in art literacy, but mostly left to themselves to produce work in an environment that utilizes the philosophy of creativity as play. Known to his students as simply, “Clark,” he would often reference simple yet profound quotes that seemed to sum up his outlook on art and life. Such as, “Only by chancing the absurd, may one hope to achieve the sublime”( Jay Defeo) or “Hygiene is the religion of fascism” (Paul McCarthy). It is with this mentality that plenty of Richert’s students have gone on to be successful in Denver and elsewhere.

As young and curious art students at the University of Kansas in the early sixties, Richert and his like-minded peer, Gene Bernofsky developed a conceptual art style known as “Drop Art.” These “droppings” were informed by the “happenings” of Allan Kaprow, the fluxus experiments of free thinking performance artists like John Cage and Merce Cunningham, the social absurdism of Robert Rauschenberg, and the progressive philosophical science of Buckminster Fuller, all of whom attended and worked at Black Mountain College, which as an institution of creative thought was well ahead of its time.

Drop Art “droppings” began quite literally as young Richert and Bernofsky started painting rocks and dropping them off a loft roof onto a main street of downtown Lawrence, Kansas, noticing the puzzled reactions of people passing by. Soon, everything that the artists created or did became Drop Art, and as the question arose, “what to do after school?” the likely decision, as of course, no one wanted jobs, was to continue “dropping.”

It was at this time that Richert and Bernofsky created a live-in work of Drop Art outside of Trinidad, Colorado known as Drop City. The year was 1965, before Timothy Leary “dropped out” and before dropping acid was in vogue. Drop City became the first artist community/commune of its kind. Dividing the entire property into triangles, a work of Drop Art was built at each vertex mostly made from free materials and junk. The artists lived in hand-built domes based on the architectural ideas of Buckminster Fuller and Steve Baer, who’s “triacontahedron” and “zonohedra” became their studios and homes.

As a legally incorporated artist community, Drop City’s purpose was to house, feed, and provide studio space for artists, and in this it was largely successful. At the time, this was (and still is) a very radical concept. All you had to do was just show up to become a part of Drop City; no one paid any rent and it was extremely open. It was basically a social experiment before anything else. Residents were not even required to work to stay there! At its peak, there were about 40 residents at Drop City. At this time, a good amount of money was coming in to support this social Drop Art. For the first few years, the artists were selling work and there was a great deal of interest in Drop Art in the art world. Richert also traveled around the country doing what he called “light shows,” which were performances where they gave lectures and talked about Drop City to galleries, schools and universities, and also showed “The Ultimate Painting,” which was a circular painting that rotated on motors, with its rotations per second synchronized to flashing strobe lights to create various visual effects.

Around this time, members of Drop City participated in a major show in the Brooklyn Museum that was organized by Robert Rauschenberg entitled “Engineering Art and Technology.” Members of Drop City also worked for a poster design company in New York, designing psychedelic geometric Drop Art posters. Since its time, Drop City has become very well known for being the “first hippie commune,” and for other reasons such as their early use of sustainable energy sources like solar power. It was a period of Richert’s life that he looks back on with great fondness, remembering the synergetic interaction between artists and residents to create experimental artistic expression.

Drop City was the birth of such innovative companies and endeavors as Zomeworks, an early solar energy company; Criss Cross, another artist group based in Colorado and New York, with whom Richert was affiliated; and the development of the “61-zone system” by Zometools, which is a Denver-based company that grew out of Zomeworks. In 1967, Drop City won Buckminster Fuller’s Dymaxion award for innovative and economic housing construction.

In my interview with Richert, he spoke so highly of his experiences at Drop City, that it is a current goal of his to develop another creative-person community as soon as this year. In this artist community you could either own part of it, or stay there rent free. He is currently looking for land or property close to Denver to create a model of sustainability, possibly in an urban setting. Embodying the sprit and philosophy of the original, ideally this new “Drop City” would be one of many places like it around the world and would exist in an interconnected network of artist communities. There will be uses of geodesic domes, sustainable solar heating and wind energy, along with an efficient use of water. It would exist as a space for artistic freedom and experimentation, with the main emphasis being on the idea that when you have interaction between the people, you get a result better than an individual could produce.

Richert’s current work has its roots in the time period surrounding Drop City and the mathematical discoveries that took place during his stay there. Currently, a retrospective on Richert’s work will be opening on February 5th, and running through the month in the Steele Gallery on the RMCAD campus. The show covers a long period of time in the artist’s life, with the oldest piece in the show being completed in 1964. The exhibition is divided up into a series of paintings done over the years, with at least one painting from each of the series since 1964.

Richert’s visual work has much to do with the scientific and mathematical realms, and the idea that the basis of reality is in mathematical relationships. Still, it seems that Richert is much more at home as an artist rather than as a scientist or a mathematician, an artist that is able to work with scientific ideas, but not be bound by their limitations.

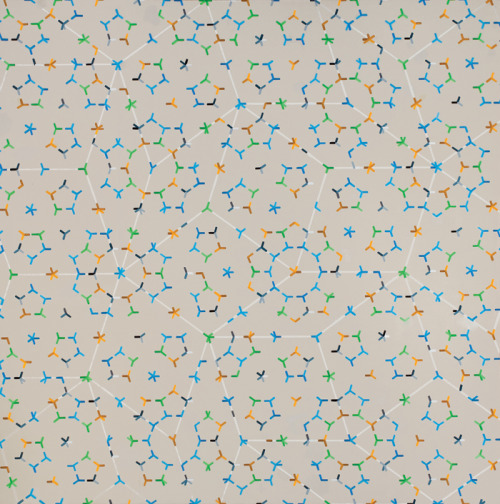

Richert’s paintings that work with various “non-periodic tessellations,” which are non-repeating geometric patterns, are an example of the extreme scientific side of his mind and the more poetic and spiritual side working together; the paintings seem to resemble tessellations out of an Islamic mosque.

There is a blurred line between poetry and mathematics in Richert’s work that in my opinion is one of the most magical things about his painting. Richert often tells of how seeing a Mark Rothko abstract expressionist painting as a youth moved him to tears and made him want to pursue a life in art instead of science.

What may prove to be one of Richert’s masterpieces, which will be in his RMCAD exhibition, is a video animation projected on an enormous hand-made hemispherical screen that he has been working on for years. This will be accompanied by a background track of what the artist calls “Cheesy rhythms.” In Richert’s own words, “it is an animation showing a type of motion that postulates as to what underlies physical reality. Rotating helixes produce motion that is like Brownian motion, but is not Brownian motion, it is C-motion, the “C” standing for Clark, naturally.” (Brownian motion is the seemingly random movement of particles on a sub-atomic level).

When speaking with Richert, it is clear that you are in the presence of a very humble man who is home to an incredible mind—an incredible mind, with an incredible history; a mind with a passion for life and art and the way things work. That passion carries over into everything he does and everyone he meets, as anyone who knows him can attest to. His singular influence on the city of Denver and the state of Colorado in general is more than impressive. As his career reaches maturity, he is not slowing down; he only seems to have more ideas, goals and desires than ever before; he only seems ever closer to understanding the nature of reality.

“1960’s to Present” runs from February 5th- March 12th 2010 in the Philip J. Steele Gallery at the Rocky Mountain College of Art and Design.

www.clarkrichert.com

www.rulegallery.com

www.rmcad.edu/gallery-exhibitions