Personal Profile: Laying Tracks with Jack McConaha

Published October 2009 Vol. 13 Issue 9

by William Hillyard

Jack McConaha answered my knock in a white t-shirt. “Come on in; have a seat,” he said. “Say hello to the kids.”

His ‘kids,’ two toy poodles, yipped at me from the side of the king-size bed that practically fills the windowless living room of his sprawling Wonder Valley cabin. The dogs’ bed and food and water bowls sat in the rumpled covers. The whoosh of the swamp coolers covered the room with a blanket of white noise, reducing the TV at the foot of the bed to a murmur.

Jack disappeared to finish dressing. “Must have picked up a nail,” he shouted from deep within the warren of the house. “I checked the air in my tires this morning and one was a little low.” It seemed he was continuing a conversation that had begun before I arrived. “Don’t matter,” he went on, “it’s just down a couple of pounds.”

Chatting constantly, he told me he doesn’t like the Firestone tires that came on his new patrol Jeep. He’s going to replace them, he said; get BF Goodriches—they self-seal if you get a puncture.

Jack reentered the room dressed for his desert patrol; summer weight camouflaged fatigues—Marine Corp issue—draped from his short, stout frame, a 40-caliber Smith and Wesson on his hip. The tin badge on his breast designated him “Captain of Security.”

Jack’s hand, resting on the grip of his pistol, showed the faint scars of the welding accident that earned him his lifetime of disability checks, the money he has lived on for his nearly 40 years in Wonder Valley.

He came to this hardscrabble desert enclave when it was still largely peopled by pioneering “jackrabbit homesteaders” brought to this area by the Small Tract Homestead Act of 1938, which carved Wonder Valley into five acre parcels free for the taking. All you had to do was to “prove up” your parcel: clear the land, build a cabin. When Jack arrived here in the early 1970s, some four thousand cabins flecked this remote patch of desert. These days only a thousand or so still stand—and half of those sit vacant. The remaining few house the snowbirds and retirees, artists and writers, drifters and squatters that live out here along Wonder Valley’s nearly 400 miles of washboard roads.

Jack volunteered as a fireman when he first arrived; even did a stint as chief of the area’s small all-volunteer brigade. Now he’s the one-man security force patrolling the valley’s lonely roads. Some people come to these abandoned cabins and empty desert from “down below,” from L.A. and that mess down there by the coast, to cook up drugs or dump a dead body or just wander out into the saltbush scrub and blow their own brains out. Jack told me about the Wonder Valley man he came upon, standing in the sandy lane, bashing his wife’s head with a rock. He told me about the meth labs he busted, the all night stakeouts, the search and rescues. He told me about the people he’s helped, how they tell him how much they appreciate what he does. He talked of the commendations he’d been awarded, citations, newspaper clippings, the luminaries he met in the line of duty as the self-appointed guardian of this remote corner of the Mojave Desert.

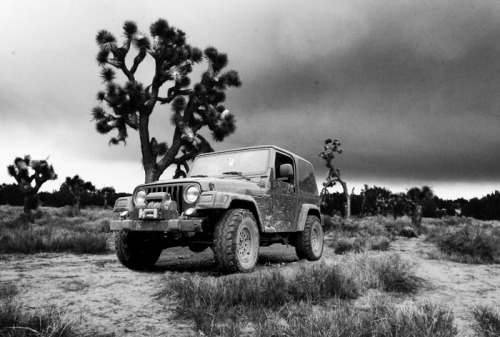

We climbed into Jack’s Jeep and into a nest with barely room for the two of us. I ride shotgun with my feet propped on a metal first-aid kit and my head nestled in the mass pushing against me from behind the seat: blankets and jackets, shovels and jacks, jugs of water and gas, anything he might need while on patrol in the desert. The police scanner crackled to life as we threaded through the clutter of mining equipment on his five acre parcel, the rusting metal, old car parts, wooden contraptions arranged into a life-size diorama of a turn-of-the-century gold mine. We passed through the locked gate, through the wall of wind-ravished tamarisk trees and past the Marine Corp flag flapping wildly in the furnace-hot breeze, turning out onto the lattice of dusty dirt roads that divide Wonder Valley into the empty rectangles of greasewood and snakeweed. The roads had been plowed that morning, the usual washboards smoothed, the golden sand silky as softened butter under the harsh sun. “I’ve got to talk to that tractor driver,” Jack mumbled in jest, “He’s erased all my tracks!”

The trackless roads took us past the remains of old homestead cabins, stripped and bare, their windows gouged out, doors agape, each yawning a lifeless grimace over the bleak desert landscape. They dot this barren grid like strange game-board houses in a dystopian version of Monopoly. All the while Jack chattered: “This place back over here belonged to Margaret Malone.” He circled around the small house, leaving his tire tracks on the scoured sand. “Margaret Malone, her place used to be known as the purple mansion ’cause it had all kinds of purple rocks. See all them purple rocks?” he asked, pointing to a line of cobbles painted a faded lilac, mostly buried by the wind-blown sand. “All them purple rocks—she had rocks everywhere—they made the place look like shit.”

Each parcel had a story, the story of a mid-century homesteader who came to Wonder Valley, cleared the land, built a cabin, an outhouse. They endure the whipping wind, the crackling heat, the desiccating dryness as lifeless shells. We drove onto each one, circling the shack before driving to the next.

“This place here belonged to Vera Sabrowski’s daughter, Anita,” he rambled, as we bounced around another vacant place. He rattled off names and genealogies, channeling ghosts from the past. “Vera owned that house back there where that pile of furniture was.” We passed the skeleton of a dog lying against the house, its choke-chain still around its neck.

At another boarded-up shack: “Oh and this one here, a lady had it. I came by here one day and a guy was coming out with stuff, so I held him at gunpoint for about five minutes,” he chuckled. “He’d bought the place for back taxes.”

He keeps his gun holstered these days. Drawing a bead on a couple of area kids a few years ago got him two years probation for brandishing a weapon. He hadn’t recognized the kids; they’d practically grown up since he’d seen them last. He stopped them coming from the direction of a burglarized cabin. Their parents called the police; Jack was arrested, his guns confiscated. These days, the sheriff prefers Jack carry his pistol unloaded.

In the Jeep, we crept through another cluster of cabins while Jack continued to talk: “And those two over there, there’s some kind of battle in court over them. Matter of fact, technically, I got no right on this property.”

He drove between the shacks, laying tracks through what in suburban America would be the front yard.

“All I do is I go put some tracks and somebody calls the sheriff or something and—the sheriff pretty well knows my tire tracks—well, they don’t know these; these are the Firestones tires, they’re different than the others.”

Jack talked a lot about tire tracks. He told me about tracking criminals back to the scenes of crimes, about photographing tracks to deliver to the sheriff as evidence only to have it ignored or lost or forgotten. He lays tracks so the place appears occupied, visited, cared-about. He recognizes his own tracks as he drives around the lonely cabins; he looks for others crossing over his. Cabin after cabin, his were the only tracks.

“This one over here,” he said, quickly shifting to another shack and another story, “Steve Staid—his dad and ma had the place—they gave Steve their place, they let him come out here, and he got so juiced and screwed up, I had to call an ambulance. He was about two days from dying from booze and dehydration. We just about lost him.” He paused a moment, lost in a thought. “I felt real bad about that. I’ll put some tracks in it.”

Circling through the property, he laid a trail in the dirt and dust, marking the parcel, giving it a pulse, a sign of life.

Suddenly, a dust devil’s mushroom cloud caught Jack’s eye. “I thought that was smoke,” he laughed shielding his eyes against the sun. His years as a volunteer fireman keep him alert to the threat of fire. “Oh, but there ain’t nothing over that way.”

The rising column of dust sparked stories of the friends Jack lost in fires. Most perished out here because they couldn’t escape the flames, they died trapped by piles of rat-packed papers and junk-become-tinder in their homes.

Then there was the murder-suicide a couple of months ago. But Jack didn’t see the smoke or even hear the explosion that shook the valley and ripped Tammy McMurray’s house apart, incinerating her and her husband Stewart. Though Jack’s home is only about a mile away, he’d been working on his Jeep, banging and welding so he even missed the calls on the scanner. He didn’t arrive until the fire was well out.

Jack broke off his story as we approached the ruins of a homestead cabin virtually buried in scavenged refuse. “Here’s what ya get faced with out here,” he said, thumbing at the shanty.

The bare dirt lot was covered with remnants of plywood and scrap wood cobbled together into make-shift lean-tos and corrals of pallets littered with rubble. No water, no electricity, it looked more like a stockyard than a home. A silhouette stared back at us through a glassless window. “They ain’t got nothing,” Jack muttered, his tinge of sympathy quickly replaced by disgust. “We give them water and helped them, give them food and helped them, but that’s when they first moved in, but now they’ve got all that shit there. We’ve just sort of ignored it so far,” he said. We’ve left them alone.”

I wondered who he meant by ‘we.’ That shape in the window was the only other soul I saw in three hours of laying tracks. The artists and writers and snowbirds and retirees were gone for the summer, escaped to cooler climes, visiting the grandkids, spending time on the coast. Even The Palms bar was closed.

I thought about that person sitting out there in that cobbled-together shack. Inside the Jeep, the thermometer read 115. I was sweating, the air conditioning overpowered by the roasting heat. You could die out here. Like the guy whose car broke down on Godwin Road a couple years ago or the one who got stuck scrapping on the Marine Base or that woman in that old broken-down bus. “We knew she wasn’t gonna make it,” Jack replied.

Jack stopped the Jeep on a hill overlooking Wonder Valley. The sky was white with dust; the distant mountains floated in a silver mirage that danced with a shower-glass shimmer in the stifling heat. He pulled a juice bottle filled with ice water from behind his seat and poured himself a glass. He fell silent and, as the Jeep idled, the furnace-hot breeze worked to erase his tracks.•